Introduction The

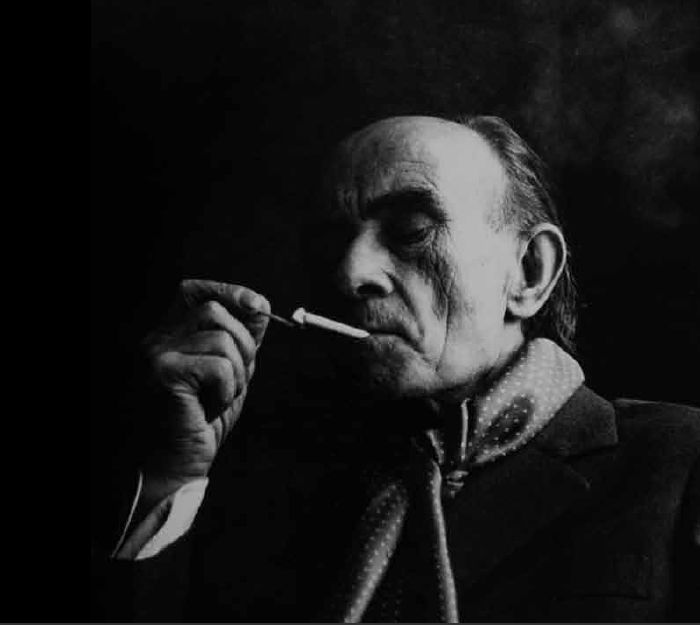

Kassák Museum’s permanent exhibition presents the literary, artistic

and journalistic oeuvre of Lajos Kassak (1887-1967), the leading figure

of the Hungarian avant garde. Independent in thought and action, he

first appeared in the 1910s as an artist of a type that was utterly new

in Hungary, and his responses to historical and social challenges

through the successive stages of his life were unceasingly original.

Born into a half-Magyar, half-Slovak family, with no scholarly

background, he developed his own way of thinking, innovative and

wide-ranging, and from his own strengths alone grew into an

The

Kassák Museum’s permanent exhibition presents the literary, artistic

and journalistic oeuvre of Lajos Kassak (1887-1967), the leading figure

of the Hungarian avant garde. Independent in thought and action, he

first appeared in the 1910s as an artist of a type that was utterly new

in Hungary, and his responses to historical and social challenges

through the successive stages of his life were unceasingly original.

Born into a half-Magyar, half-Slovak family, with no scholarly

background, he developed his own way of thinking, innovative and

wide-ranging, and from his own strengths alone grew into an

international

authority. He never ossified into the pose of artistic giant, and his

strong individuality kept him open and dynamic, able to collaborate, and

think collectively. Communities grew up around him – the people who

worked with him in editing journals, a cultural society, and a walking

group where young working-class people shared experiences and visions of

the future. Kassák was a pioneer of the modern attitude that artistic

activity is not constrained by the boundaries of aesthetics: he created

art which linked social criticism with bold ideas for the future.

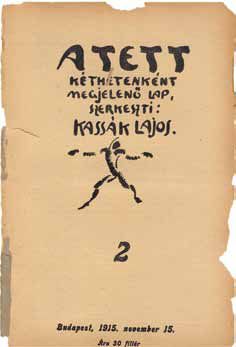

Kassák’s periodicals in the 1910s and 1920s A

Tett, 1915 – 1916 Kassák started up his first journal, A Tett (“The

Action”), during the First World War. A Tett had a tone and a European

perspective which the public of the time found provocative. Its models

and precursors were German journals with social and political

inclinations, and Dadaist-influenced publications. Although the journal

became the target of numerous political attacks for its anti-war

rhetoric and anarchist views, its propagation of radical ideas on the

purpose of art succeeded in encouraging the embryonic artistic avant

garde and the activist movement. It was in A Tett that Guillaume

Apollinaire and Marinetti were first published in Hungary. A Tett

survived for a total of 17 issues between 1 November 1915 and October

1916. Kassák devoted the last, international issue to works and writing

by artists from countries at war with the Monarchy. The prosecutor’s

office responded by finally closing it down. A Tett’s other editors

included Dezső Szabó, Aladár Komjáth, Mátyás György, József Lengyel,

Andor Halasi, János Mácza, Vilmos Rozványi, Imre Vajda and Béla Uitz.

A

Tett, 1915 – 1916 Kassák started up his first journal, A Tett (“The

Action”), during the First World War. A Tett had a tone and a European

perspective which the public of the time found provocative. Its models

and precursors were German journals with social and political

inclinations, and Dadaist-influenced publications. Although the journal

became the target of numerous political attacks for its anti-war

rhetoric and anarchist views, its propagation of radical ideas on the

purpose of art succeeded in encouraging the embryonic artistic avant

garde and the activist movement. It was in A Tett that Guillaume

Apollinaire and Marinetti were first published in Hungary. A Tett

survived for a total of 17 issues between 1 November 1915 and October

1916. Kassák devoted the last, international issue to works and writing

by artists from countries at war with the Monarchy. The prosecutor’s

office responded by finally closing it down. A Tett’s other editors

included Dezső Szabó, Aladár Komjáth, Mátyás György, József Lengyel,

Andor Halasi, János Mácza, Vilmos Rozványi, Imre Vajda and Béla Uitz.

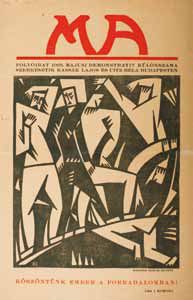

MA, Budapest 1916 – 1919 After

A Tett was banned, Kassák launched a new journal, MA (“Today”). MA came

out in Budapest 35 times from 15 November 1916 to 1 July 1919, edited

by Kassák, Béla Uitz, Sándor Bortnyik, Jolán Simon, Sándor Barta and

Erzsi Ujvári. The journal’s subtitle changed several times – originally

Journal of Literature and the Arts, then Activist Journal, and finally

Activist Journal of Arts and Social Affairs – indicating its intended

role in the historical developments of the late 1910s. During the

Republic of Councils, Kassák stood up for the autonomy of art and became

embroiled in an ideological dispute with Béla Kun. The journal was

banned. The fall of the Republic of Councils brought even worse times

for Kassák: after a period of imprisonment he – together with many other

intellectuals – left the country in 1920 and took up a life of exile in

Vienna. During these years in Budapest, Kassák and the MA Circle

engaged in organisational activities which went far beyond editing a

journal. Through their books, exhibitions and cultural events, they

assumed the task of propagating ideas that spanned art, literature and

music.

After

A Tett was banned, Kassák launched a new journal, MA (“Today”). MA came

out in Budapest 35 times from 15 November 1916 to 1 July 1919, edited

by Kassák, Béla Uitz, Sándor Bortnyik, Jolán Simon, Sándor Barta and

Erzsi Ujvári. The journal’s subtitle changed several times – originally

Journal of Literature and the Arts, then Activist Journal, and finally

Activist Journal of Arts and Social Affairs – indicating its intended

role in the historical developments of the late 1910s. During the

Republic of Councils, Kassák stood up for the autonomy of art and became

embroiled in an ideological dispute with Béla Kun. The journal was

banned. The fall of the Republic of Councils brought even worse times

for Kassák: after a period of imprisonment he – together with many other

intellectuals – left the country in 1920 and took up a life of exile in

Vienna. During these years in Budapest, Kassák and the MA Circle

engaged in organisational activities which went far beyond editing a

journal. Through their books, exhibitions and cultural events, they

assumed the task of propagating ideas that spanned art, literature and

music.

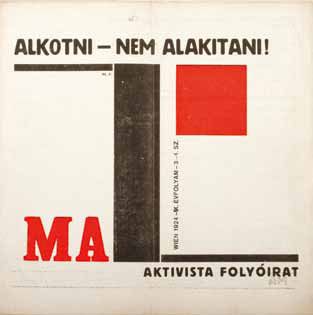

MA, Vienna 1920 – 1926 In

1920, MA was relaunched in the very different cultural milieu of

Vienna. Exile caused the journal to take on a new perspective. Kassák

quickly entered the international network of avant garde journals, and

within a few years became a respected figure of European modernism. He

became acquainted with Kurt Schwitters, Tristan Tzara, El Lissitzky and

Hans Arp. Several of the friendships he forged with artists at that time

persisted to the end of his life. It was in this milieu that Kassák

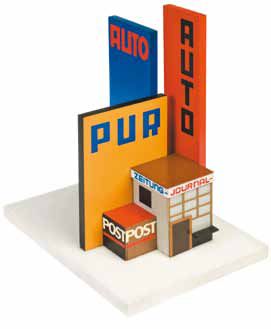

became an artist and a committed disciple of Constructivism. In 1924, he

exhibited in the Sturm Gallery in Berlin. His theoretical work also

developed during his years in Vienna. He wrote the theory of Image

Architecture, and was an active participant in the international

discourse of contemporary art.

In

1920, MA was relaunched in the very different cultural milieu of

Vienna. Exile caused the journal to take on a new perspective. Kassák

quickly entered the international network of avant garde journals, and

within a few years became a respected figure of European modernism. He

became acquainted with Kurt Schwitters, Tristan Tzara, El Lissitzky and

Hans Arp. Several of the friendships he forged with artists at that time

persisted to the end of his life. It was in this milieu that Kassák

became an artist and a committed disciple of Constructivism. In 1924, he

exhibited in the Sturm Gallery in Berlin. His theoretical work also

developed during his years in Vienna. He wrote the theory of Image

Architecture, and was an active participant in the international

discourse of contemporary art.

MA ultimately survived for 10 years, making it the longest-lasting journal with such a modern outlook in the period.

(You can find the issues of MA in Vienna in the digital archive of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.)

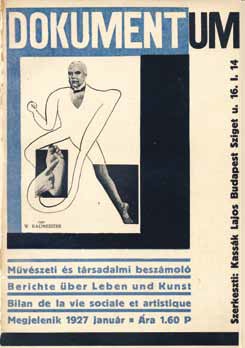

In

the second half of the nineteen twenties, together with European

modernism in general, Kassák and MA found themselves increasingly in a

vacuum. Kassák returned home in autumn 1926, and in December of that

year launched a new journal, Dokumentum. His main colleagues in this

project were Tibor Déry, Gyula Illyés, József Nádass and Andor Németh.

As with MA, Kassák placed Dokumentum in the international perspective,

as evidenced by its appearing in three languages: Hungarian, German and

French. Kassák wanted to make up for the deficit of information on

contemporary European art by publishing foreign writers. He extended his

interest to modern architecture, music and dance, and particularly to

film. Kassák was the first to present contemporary Russian art in

Hungary. The journal’s compass went well beyond the accepted boundaries

of art of the time. It gave space to new lines of enquiry like the

multifaceted study of society and social issues in art. The public of

the time, however, was not receptive to this new approach, and

Dokumentum petered out after a year.

In

the second half of the nineteen twenties, together with European

modernism in general, Kassák and MA found themselves increasingly in a

vacuum. Kassák returned home in autumn 1926, and in December of that

year launched a new journal, Dokumentum. His main colleagues in this

project were Tibor Déry, Gyula Illyés, József Nádass and Andor Németh.

As with MA, Kassák placed Dokumentum in the international perspective,

as evidenced by its appearing in three languages: Hungarian, German and

French. Kassák wanted to make up for the deficit of information on

contemporary European art by publishing foreign writers. He extended his

interest to modern architecture, music and dance, and particularly to

film. Kassák was the first to present contemporary Russian art in

Hungary. The journal’s compass went well beyond the accepted boundaries

of art of the time. It gave space to new lines of enquiry like the

multifaceted study of society and social issues in art. The public of

the time, however, was not receptive to this new approach, and

Dokumentum petered out after a year.

The Munka Ci rcle (1928 – 1934)

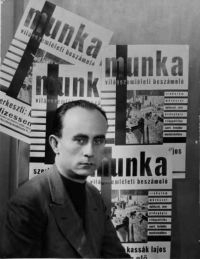

Driven

by his vision of the workers as a force for transforming society,

Kassák took up the cause of workers’ education in the late 1920s.

Setting himself the goal of educating young people in

class-consciousness

and solidarity, he founded the journal Munka [Work] in 1928 and brought

together students and young workers into what became known as the Munka

Circle. Kassák gradually built up the Kulturstudió (“Cultural Studio”),

approaching worker education as a whole way of life, through a unity of

organised activities, entertainment, recreation and education. His

ambitious aims drew contributions from several fine teachers and

artists. Jolán Simon organised a speaking choir, Sándor Jemnitz a

modern- music chamber chorus, and György Justus a folk-song choir based

on Bartók-Kodály principles. The painting group of the Circle was led by

students of the Academy of Fine Arts – Béla Hegedüs, György Kepes,

Dezső Korniss, Ernő Schubert, Sándor Trauner and Lajos Vajda – whom

Kassák had met at a joint Schubert-Trauner exhibition in the Mentor

Bookshop. The Munka Circle was a culturally and politically open group,

and its members constantly brought with them more and more new people,

friends and colleagues.

The spirit of the Munka journal, and the

subjects of its articles, focused on the social reality of the time

rather than the issues of art itself. Most of the essays published in

Munka were based on

the world of fact, and social analysis, technical

progress, collective action and physical culture were constant themes.

The format of the journal and its low price also served to bring this

information to as wide a readership as possible. The

Circle was eventually brought to an end by an Interior Ministry decree

of 1934. The Kulturstudió and other national speaking choirs and

cultural groups were banned, but the disintegration of the Munka Circle

was accelerated by internal tensions. Munka was able to carry on

publishing for another five years, until 1939, maintaining throughout

the highest standards of any left-wing journal. Its articles criticised

fascism and Stalinism, and attempted to propagatethe message that

without culture, the masses were vulnerable to manipulation by extreme

political forces.

The

Circle was eventually brought to an end by an Interior Ministry decree

of 1934. The Kulturstudió and other national speaking choirs and

cultural groups were banned, but the disintegration of the Munka Circle

was accelerated by internal tensions. Munka was able to carry on

publishing for another five years, until 1939, maintaining throughout

the highest standards of any left-wing journal. Its articles criticised

fascism and Stalinism, and attempted to propagatethe message that

without culture, the masses were vulnerable to manipulation by extreme

political forces.

In the 1930s, Kassák started to take an

interest in photography as a documentary medium, although he did not

take photographs himself. The intellectual milieu of Munka nurtured the

Hungarian sociophotographic movement, which was active between 1930 and

1932. During this period, it held the first Hungarian sociophotographic

exhibition and published the first Hungarian sociophotographic book, A

mi életünkből (From Our Lives). This marked the end-point of two years

of collective studio work which had resulted in several publications at

home and abroad, three exhibitions in Budapest, and two abroad.

Photomontage The

exhibition’s section on the Munka Circle includes Kassák’s

photomontages, aimed at conveying how social movements (and not just the

workers’ movement) related to visuality. The demands of accessibility

and visibility and the use of the most advanced means of communication

were basic criteria for Kassák’s workingclass culture-building

manifesto. The montage, powerfully persuasive and easily interpreted,

served as a visual channel for these efforts. Its visual language proved

more effective and communicative than any pamphlet, appeal or

manifesto.

The

exhibition’s section on the Munka Circle includes Kassák’s

photomontages, aimed at conveying how social movements (and not just the

workers’ movement) related to visuality. The demands of accessibility

and visibility and the use of the most advanced means of communication

were basic criteria for Kassák’s workingclass culture-building

manifesto. The montage, powerfully persuasive and easily interpreted,

served as a visual channel for these efforts. Its visual language proved

more effective and communicative than any pamphlet, appeal or

manifesto.

After the Second World War In

the brief democratic interlude following the Second World War, Kassák

became actively involved in public affairs as vicechairman of the Arts

Council, a consultant body to the Ministry of Religion and Education,

editing its journal Alkotás (1947–48). This represented progressive

views, domestic and European, in the broadest sense. In the same years

he also edited Kortárs, a literary and social affairs journal attached

to the Social Democratic Party. In 1947, Kassák became a member of

Parliament for that party. Both journals were closed after the Communist

takeover, and Kassák was excluded from both public and intellectual

affairs. This effectively marked the end of the prominent role he had

played as a shaper of social and artistic life for several decades. His

house in Békásmegyer became a place of exile and solitude. His official

treatment changed only after 1956, when he became accepted as a writer,

but still had no outlet as an artist. The works of his later artistic

period and the phases of literary canonisation appear in this exhibition

only as markers, but the digital exhibits present these in more depth.

In

the brief democratic interlude following the Second World War, Kassák

became actively involved in public affairs as vicechairman of the Arts

Council, a consultant body to the Ministry of Religion and Education,

editing its journal Alkotás (1947–48). This represented progressive

views, domestic and European, in the broadest sense. In the same years

he also edited Kortárs, a literary and social affairs journal attached

to the Social Democratic Party. In 1947, Kassák became a member of

Parliament for that party. Both journals were closed after the Communist

takeover, and Kassák was excluded from both public and intellectual

affairs. This effectively marked the end of the prominent role he had

played as a shaper of social and artistic life for several decades. His

house in Békásmegyer became a place of exile and solitude. His official

treatment changed only after 1956, when he became accepted as a writer,

but still had no outlet as an artist. The works of his later artistic

period and the phases of literary canonisation appear in this exhibition

only as markers, but the digital exhibits present these in more depth.

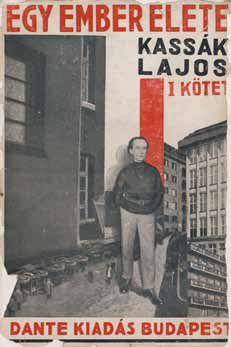

Literary work The

visual presentation of Kassák’s literary work forms As part of its

all-embracing approach to Kassák’s wide-ranging activity, the exhibition

includes a visual presentation of his literary work, journalism and

criticism. The chronology of work published during his life gives a good

picture of both his activities as a writer and his periods of silence.

The regular republication of some of his books indicates the growing

appreciation of his writing, and the titles also reveal the subjects and

approaches that preoccupied him at various stages of his career. Since

Kassák designed many of his own book covers, these also give an

impression of his changing artistic outlook.

The

visual presentation of Kassák’s literary work forms As part of its

all-embracing approach to Kassák’s wide-ranging activity, the exhibition

includes a visual presentation of his literary work, journalism and

criticism. The chronology of work published during his life gives a good

picture of both his activities as a writer and his periods of silence.

The regular republication of some of his books indicates the growing

appreciation of his writing, and the titles also reveal the subjects and

approaches that preoccupied him at various stages of his career. Since

Kassák designed many of his own book covers, these also give an

impression of his changing artistic outlook.

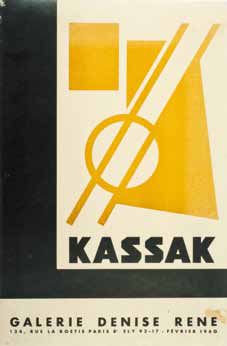

Kassák’s reception as an artist Although

the Kádár-era cultural authorities recognised Kassák as a writer and

rewarded him with the highest state honours, they never accepted his

artistic output during his lifetime. His life’s work went on display in

Hungary only once, a few months before his death, at his own expense,

and in the humble surroundings of the Adolf Fényes Room in Budapest.

Although

the Kádár-era cultural authorities recognised Kassák as a writer and

rewarded him with the highest state honours, they never accepted his

artistic output during his lifetime. His life’s work went on display in

Hungary only once, a few months before his death, at his own expense,

and in the humble surroundings of the Adolf Fényes Room in Budapest.

By

contrast, international developments brought him renewed recognition in

his old age. In the 1960s, Western art historians and art dealers alike

rediscovered the Eastern European avant garde. This resurgence of

interest launched Kassák back into the European artistic current. In his

final years, his works appeared in several individual and collective

exhibitions, mainly in Western Europe.